|

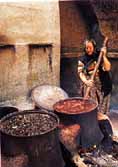

Kazanın

başında elindeki sopayla var gücüyle karıştırıyordu ipleri.

Terini sildi elinin tersiyle. Eşine seslendi: Bir kova daha su;

birazcık da ceviz kabuğu.... Bir saatlik uğraşın sonunda

kan-ter içinde kaldı. Çay molası zamanı dedi;

|

|

|

|

işini bırakıp

mutfağa geçti. Çaylar içildi; esprili söyleşiler eşliğinde...

Başka bir işi daha vardı: Okul Aile Birliği toplantısı var

da.... İş giysilerini bir yana bırakıp. modern giysileriyle

minibüsün direksiyonuna geçip gözden kayboldu. Arkadan eşine

Bir saat sonra gelirim dediği duyuldu belli belirsiz. Okul

Aile Birliğindeki sorumluluğunu yerine getirip döndü Songül

Tokmak; beş dakika sonra iş giysileriyle kaldığı yerden tekrar

işe koyuldu; eşine seslendi: Nerede kalmıştık? Songül ve

Ömer Tokmak, iş yerinin hem işçisi hem de patronuydular. Üstelik

inatla dededen-nineden öğrendikleri doğal bitkilerle yünleri

boyayıp, yöredeki tezgahlarda halı dokutuyorlardı. Ömer Tokmak

da adeta işine aşıktı. Doğadan özenle topladığı bitkileri

ayrı ayrı çuvallara doldurmuş, sırası geldiğinde onları

istediği renklere dönüştürüyor, ipleri boyayıp kuruması için

duvarlara asıyordu.

|

|

İşyeri

olarak kullandıkları mekan eski bir Avanos evi. Geniş bir avlusu

var. Boyama yapılan yer avlunun bitişiğinde. Köylerden toplanan

yünler burada çıkrıklarda eğirilip, bitki kökleri, yaprakları

veya kabuklarıyla boyanıp, kurutulup çileler haline

|

|

getiriliyor.

Aile dışında tek yardımcıları yaşı yetmişi bulmuş komşuları;

komşu teyzeleri hem eğirme işini yapıyor hem de boyanmış-kurumuş

ipleri çile halıne getiriyor. Avlunun kuzey bölümünde başka

bir kadın, yılların eskitemediği bir tezgahta halı dokuyor.

Bu

eski Avanos evi bir halı fabrikası değildi ama bir fabrika gibi

de çalışıyor: Turistlere el emeği, alın teri, göz nuru halılarımızın

geleneksel yöntemlerle yapılışını, tüm aşamalarını burada

sergiliyoruz; bir de acı kahvemizi içiyorlar bu avluda... diyor

Ömer Tokmak. Adeta bir aile şirketi gibi çalışıyor

Tokmak ailesi; çocukları da destek veriyor ana babalarına. Kimi

zaman ipleri boyayarak, kimi zaman da yabancı turistlere tercümanlık

yaparak... Ve ekliyor Ömer Tokmak: Avanosta 30 yaşına gelmiş

bir insana sorun; kadınsa halı dokur, erkekse çamurdan çanak,

çömlek yapar...

|

|

|

|

Bu

iş uzaktan göründüğü kadar kolay mıydı? Derelerden,

tepelerden bitkileri toplamak ve kendi doğal rengi dışında yün

ipleri allı-morlu renklere dönüştürmek... Bir sırrı var mıydı

bu işin? En büyük sırrı sevgi. İnsan sevdiği işte başarılı

oluyor. Yurtdışı çalışma yaşamlarının tamamlanması,

Avanosa dönmeleri... Ve dede-nine işine soyunmaları... Bu evi

restore etmeleri... Tokmak ailesinin öyküsü burada bitmiyor:

Burası bizim hem işyerimiz hem de evimiz gibi. Tüm üretim aşamalarında

biz varız. İşimizi alın terimizle yoğuruyoruz. Bitkileri

mevsiminde toplamak gerekiyor. Ceviz kabuğu, cehri, yapışkan ot,

meyan kökü, ennig (hava cıva otu)... Bunlar mevsiminde, zamanında

toplanıp kurutulmalıdır. Boyama sırasında belirli derecede ısıtılmış

suda bu bitkilerin karışımıyla iplik

kaynatılıp, sonra

da

|

|

|

|

durulanmalıdır. Ardından kurutulması, çilelere ayrılması. Sağ

olsun komşularımız da bize destek veriyorlar üretim aşamalarında.

Sonra da asırlık tezgahlarda dokunması... Kahverengi ceviz

kabuğundan, sarı cehriden, kırmızı yapışkan otu ve meyan kökünden

elde ediliyor. Ham yünler su dolu kazanlarda şap ile karıştırılıp

kaynama noktasına getirilip bekletiliyor, sonra da istenilen

bitkilerden istenilen renkler elde ediliyor. Ara tonlarda da zorlanmıyor

usta eller: Meyan kökü ve cehri karışımından portakal

rengini; hava cıva otundan gri ve moru; cehri sarısı ve toz

indigodan ise yeşil rengi elde ediyoruz... Ya siyah?

Siyah yünün kendi doğal rengidir; siyah renkte boyama yapmıyoruz.

Kaliteli halının, başka bir deyimle değerli halının tanımını

soruyoruz Ömer Tokmaka: Kaliteli bir halı için iyi bir yün

gerekli; esnek, kolay kırılmayan, yeterli yağ oranı olan, aşırı

kalın ya da ince olmayan ve boya tutma özelliği olan bir yün...

Doğal ortamında yıkanmalı; fazla hırpalanmadan didilmeli; sonra

da eşit kalınlıkta -elde ya da çıkrıkta- eğirilmeli...

Dokumasını da usta eller yaptıysa ortaya değerli dokuma halı çıkıyor.

|

|

Bu

sefer direksiyonun başına Ömer Tokmak geçiyor ve düşüyoruz

yollara; bu renkleri oluşturan bitkileri toplayacağız. Önce

kendi bahçelerinden cehri (meyvelerini) topluyoruz, sonra

da derelerden tepelerden hava cıva otu...

|

|

Yolumuzun üzerindeki Sarıhanda

soluklanıp Bozca Köyüne geçiyoruz. Önce çocuklar takılıyor

minibüsün peşine; Halıcı geldi... diye. Sonra da köydeki

yaşlılar ve halı dokuyan kadınlarla, kızlarla tanışıyoruz.

92 tane halı tezgahı olan Bozca Köyünde -son yıllarda verdiği

göçle- 14 halı tezgahı kalmış. Bozcanın evleri yöreye özgü

kesme taş işçiliğinin en güzel örnekleri; yörenin coğrafyasına

ve iklimine uygun yapılmış. Bir dokumacının evindeyiz; ikram

edilen acı kahveyi içmeden ayrılmak olur mu? Yeni boyanmış

ip istiyor dokumacılar ve ekliyorlar Yünler bizden; ipler halıcıdan...

Sonra da bitmiş halılar arabaya yükleniyor birer birer; binlerce,

on binlerce ilmik atılarak dokunmuş halılara biraz hüzün ama işi

tamamlamanın mutluluğu ile son kez bakıyorlar.

Ya

desenler? Sevgiyle yoğrulan desenler?.. Bazen yörenin hazır

desenlerini veriyoruz halı dokuyanlara; Arabeli, Çubuk Suyu,

Leblebili, Eli Belinde... Ya doğaçlama dokuyanlar? Genç kızlarımız

oldukça çabuk kavrıyorlar; bizim desenlerimize kendi yaratıcılıklarını

da eklediklerinde özgün desenler çıkıyor ortaya...

Ya desenlerin dili?

Biz halı dokuyacak |

|

olanların

desenlerini az çok önceden tahmin edebiliyoruz; hangi evden nasıl

bir halı çıkar... Desenlerden o anki ruh halleri ortaya çıkıyor;

sevinçli, hüzünlü, coşkulu anlar... Acılar da gizli bu

desenlerde... Sevgi ve özlemler de...

|

|

|

|

|

|

She

stood over the great cauldron stirring the yarn energetically. Then

she wiped the perspiration from her forehead with the back of her

hand and called to her husband, Another bucket of water, and some

more walnut shell. It was tiring work and she had been at it for

an hour. Time for a tea break she declared, and leaving the

cauldron went into the kitchen, where we sat drinking tea and

chatting cheerfully. Then she had another job to do; attending a

parents meeting at the school. Having changed her working clothes

for an elegant modern outfit, she got behind the wheel of the

minibus and disappeared down the road, calling out to her husband

that she would be back in an hour. On her return from the parents

meeting, Songül Tokmak changed back into her working clothes.

Now where were we? She asked her husband.

|

|

Songül

Tokmak is her husbands main assistant in the business which they

both own and work for. They resolutely continue to dye wool with the

natural dyes that they learnt to make from their grandparents. This

wool is then used for the carpets which

they |

|

|

commission from

local

weavers. Ömer Tokmak is passionately devoted to his work. He

gathers the roots, leaves and bark used for dyes himself and stores

them in sacks. When dyed the wool is hung up on the walls to dry.

Their

workplace is an old house in Avanos, in Cappadocia. It has a large

courtyard, off which is the area where they do the dyeing. Raw wool

supplied by neighboring villages is spun on spinning wheels, and

after dyeing wound into hanks. Their only assistants who are not

members of the family are two neighbors both in their seventies, one

of whom does the spinning and winding of the wool into hanks and

another woman who weaves carpets on an ancient loom in the northern

part of the courtyard.

|

|

|

|

This

old Avanos house is always bustling with activity. Not only is there

the regular work of dyeing, spinning and organizing the carpet

weaving, but they also welcome tourists who come to see how the

carpets are made, and demonstrate all the different stages of the

laborious traditional methods. And every visitor is offered a cup of

Turkish coffee in the courtyard, Ömer Tokmak tells us. The

Tokmak familys children help their parents too, sometimes by

dyeing the wool, and sometimes by acting as interpreters for foreign

visitors. Carpet weaving and pottery are the traditional crafts of

Avanos, and Ömer Tokmak says that if I were to ask anyone over the

age of 30 in Avanos about their occupation, the women would be

certain to answer that they wove carpets, and the men that they were

potters.

|

|

|

|

Was

it as easy as it seemed, I wondered, to gather wild plants and dye

the wool in the desired colors? Was there a secret to it? The

greatest secret is love, he replied. Success lies in loving

ones work. After working abroad for many years, Ömer and Songül

Tokmak returned to Avanos to take up the occupation of their

ancestors in a house which they restored themselves. This is both

our workplace and a second home. Usually my wife, the children and I

only get back to our house late at night. We are involved in all the

stages of production and work hard. The plants have to be gathered

in the right season. Dyes are made from walnut shells, the

berries of a species of buckthorn (Rhamnus petiolaris), pellitory

(Parietaria officinalis), liquorice root oriental alkanet (Alkanna

tinctoria) and many others. These are dried, and boiled in water in

various combinations to produce the desired colors.

|

|

The

raw wool is first boiled in water containing alum and then left to

soak before dyeing. When the wool has been dyed, it is rinsed and

dried. Then the wool is used for weaving carpets on traditional old

looms. Walnut shells produce the

|

|

|

color brown, buckthorn yellow, and

pellitory and liquorice root red, for example. Mixtures of the

different dye materials produce other colors, such as orange from a

mixture of liquorice root and buckthorn, and green from a mixture of

buckthorn and indigo powder. And what about black? For that we

use natural black wool not dye explains Ömer Tokmak.

We

asked him what qualities to look for in a carpet. He told us that a

good quality carpet must be made of good quality wool, pliant and

strong, containing sufficient oil, neither too thick not too thin,

and able to take the dye well. The raw wool must be washed by hand,

combed without treating it roughly, and then spun, either by hand or

using a spinning wheel. If it is then woven into a carpet by a

skilful weaver the result is a high quality carpet.

Then

we set out with Ömer Tokmak at the wheel on an expedition to gather

wild plants. We stopped first at his own garden to gather buckthorn

berries, and then headed out into the countryside to find oriental

alkanet. After a halt at Sarihan we went on to the village of Bozca.

Children pursued the minibus shouting, The carpet mans

here! We were met by the elderly people, and the women and girls

who weave carpets. There were once 92

looms in the

|

|

village, but as

many of the inhabitants have moved away to the cities, today only 14

carpet looms remain in use. The houses of Bozca are beautiful

examples of the excellent local stonework, appropriate to an area

lacking in forests and with a harsh continental climate.

|

|

|

In

the home of one of the weavers we were offered the usual cup of

coffee. The weavers asked for more dyed yarn, and explained that

they supply the raw wool which is returned to them as dyed yarn.

Finally the finished carpets were loaded into the van, and the women

looked for the last time with mingled regret and pride at the

carpets whose tens of thousands of knots they had woven with loving

care.

And

what about the designs? Sometimes we provide ready made patterns

for motifs from carpets of certain regions, such as the Arabeli, Çubuk

Suyu, Leblebili, and Eli Belinde motifs. And do any of them weave

without a pattern? Our young girls are quick to learn. When they

add their own inspiration to our designs, they produce original

pieces. We have got to know more or less what each weaver is likely

to produce. The designs are also influenced by their mood at the

time; whether they are happy, excited or sad. Sorrows are concealed

in the designs as well as love and yearning.

|

|